How to encourage healthy skepticism and common sense in your clients.

Stock markets run on information, but unfortunately, that can include misinformation—and even small bits of fake news can have a big impact. For example, fake reports of the sale of Twitter have driven rapid, multipoint increases in its stock price on several occasions. And in 2019, a fake letter supposedly from the CEO of Blackrock said the investment fund planned to divest from fossil fuel companies in the interest of climate change, causing briefs swings of hundreds of millions in dollars in its share price, according to a University of Baltimore study published that year. Overall, the study found that financial misinformation causes the loss of some $39 billion a year in the stock market.1 For producers, this means that helping clients navigate their ways through the dangers of misinformation is an increasingly important challenge.2

Financial misinformation comes from a variety of sources. At times, bad actors are behind it— individual stockholders may spread false positive news online about a company to “pump and dump” its stock to make a quick profit. Or short sellers may circulate made-up negative news to drive prices down.

Often, however, the delivery of misinformation is not so obviously malicious. An overenthusiastic expert on television may present a too-rosy picture of a company. Bloggers, looking for something interesting to say, might raise unlikely scenarios putting a company’s earnings in doubt. Or individuals may, and often do, share dubious reports with friends and colleagues without bothering to assess their accuracy.

The Power of Fake News

“If we hear the same misinformation over and over, we can start believing things that are completely outrageous.”

Why does misinformation get so much traction? Hoaxes, half-truths, and guesses about the stock market have always been around—but now, with the internet and 24-hour financial news cycles, that misinformation can be quickly spread and amplified, without context or confirmation. And the sheer speed and volume of information coming at investors can simply be too much to fully assess and process.

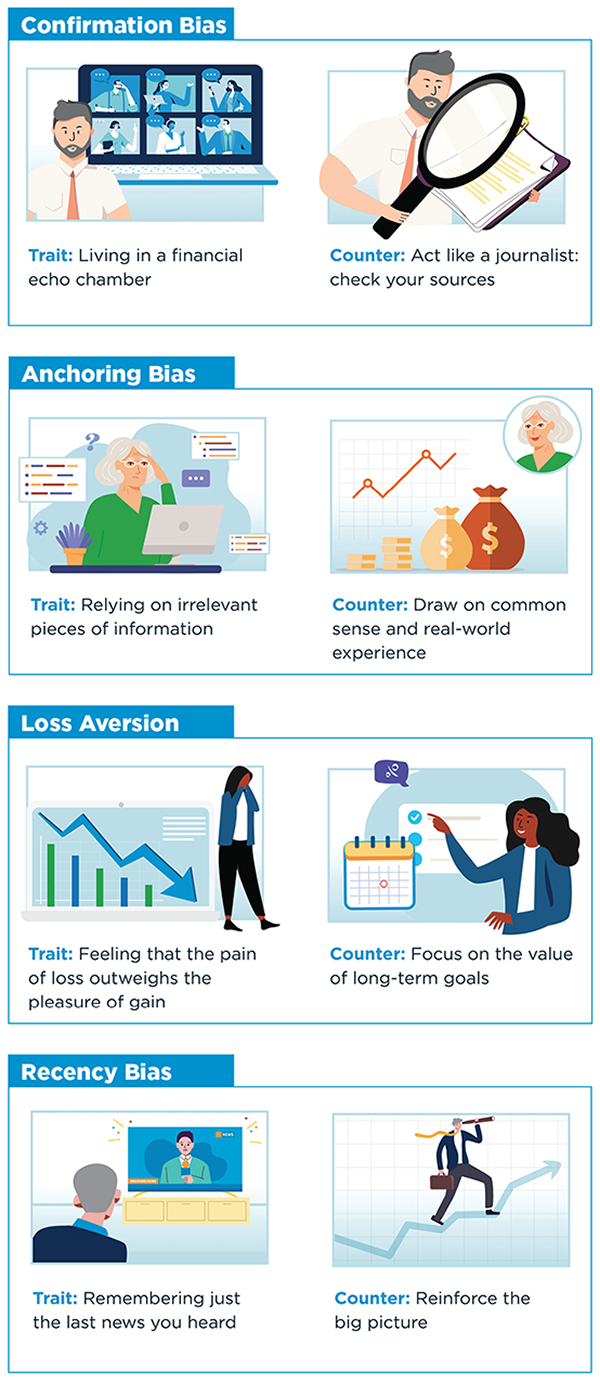

What’s more, misinformation often takes advantage of several basic psychological traits we all share. For example, confirmation bias causes us to “seek information that confirms our current opinion and ignore everything that opposes it,” says Zach Ursiny, an executive coach with Advantage Coaching & Training in Wheaton, Illinois. With social media groups and algorithms that send targeted content to individuals to fit their interests, people often end up in financial echo chambers that limit their perspective. “It can gaslight us,” he says.

With another bias, loss aversion, “We’re overly focused on avoiding losses, because psychologically, the pain of a loss is greater than the pleasure of an equal gain,” Ursiny says. That can make people more likely to believe rumors of, say, a coming major recall of a company’s products.

Anchoring bias can cause us to rely on one or two pieces of information to assess other information, even if that anchor point is irrelevant. For example, if a stock has been trading at $300 and it drops to $200, using the higher figure as an anchoring fact would make it look like an attractive buying opportunity, when in fact the stock might still be overvalued at $200.

Similarly, recency bias causes us to give more credence to the most recent information we’ve encountered. “So, clients might be more likely to remember what they saw on the news last night and forget the planning that happened in the meeting three months ago when you went through their financial plan,” he says.

Producers can help clients be more aware of those psychological biases and let them know that everyone is subject to them—it’s not just them. “Tell the client you’re not alone in being misled here,” says Ursiny. “This is powerful stuff, and you need to understand why it’s so appealing to you.”

Producers should also be prepared to counter the misunderstandings those biases create. For example, if recency bias is causing a client to focus too much on this week’s reports of a particular stock’s dramatic growth, “reinforce the big-picture view,” says Ursiny. That means getting them to think beyond the immediate past, perhaps “going back to earlier conversations about comprehensive planning and a holistic approach to their plan” to remind them that they don’t need to chase the latest hot investment. Or if an anchoring bias has led someone to see reports of huge gains from blockchain investments as a kind of baseline for performance, “point them back to their plan and their goals,” he says. “Tell them, ‘Your goal wasn’t to make a billion dollars by being extremely risky. Your goal was to provide enough money for your family, and here’s how your plan is doing that and how you’re going to hit that goal’.”

It’s important to encourage healthy skepticism, and to encourage clients to draw on common sense and real-world experience. Misinformation can be compelling and it’s important for clients to ask themselves, “does this seem reasonable, or is it unusually attractive or unusually threatening?” Because when it comes to investing, it’s useful to use an updated version of the old adage: If it sounds too good—or too bad—to be true, it probably is.

Guidelines for Clients

Producers can provide clients with several tips to help them steer clear of misinformation.

- Consider the source. What credentials does the source have—does your golfing partner really know that much about investing? Why are they saying what they’re saying? Are they trying to stir up emotions to make you buy something? Do they have their own reasons for offering their views? “When you’re watching financial experts on news channels, yes they can be exciting and entertaining,” says Jeannie Underwood-Kotner, senior vice president and head of Global Atlantic Consulting, Global Atlantic Financial Group. “But they’re not always acting in your best interest and putting the consumer first. They’re thinking about being entertaining and they’re putting advertising dollars first.” And producers can tell clients to do what real journalists do: Confirm stories that you hear with several sources before you act.

- Look for straightforward, non-emotional information. “Be proactive about asking clients where they get their news and help them understand which places are good and which aren’t,” says Underwood-Kotner. “Get them to start looking at sources like Bloomberg, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, Barron’s—places that just offer information, rather an ‘expert’ shouting ‘this stock is on fire!’” She also suggests emphasizing reading, not just watching TV. “When you’re reading, it takes out the actors and actresses with all that energy and emotion and all the wild media statements,” she says. “It’s just you, reading the facts.”

- Cut back to avoid overload. “Our judgment can be overwhelmed by too much information”, says Ursiny. “So, encourage clients to limit the time they spend watching the news—maybe 10 minutes in the morning and 10 minutes in the evening.” And make it an attractive exercise. “From a psychological standpoint, our brains really struggle with the concept of ‘don’t’—so replace ‘don’t’ with something positive. Remind them that they can then spend more time with their families and doing things they like.”

Share

Related resources

More on Expert Insights

Your Thriving

Practice

A destination to empower financial professionals to build, manage, and grow their practice

Get started with Global Atlantic

Take the next step with a company that can help elevate your business.

Need help?

Find all the contact information to submit and service your business.